In England, approximately one in seven young people meet criteria for a ‘mental disorder’, with prevalence rates rising over the past two decades. Schools, as recognised by the UK government, may provide an ideal environment to try and address this problem. They provide young people with unparalleled access to services; alleviating barriers such as time, location, and cost.

One of the most common forms of school-based mental health intervention is counselling. School-based counselling is well established in over 60 countries around the globe, and mandatory in at least 40, including Wales. In England, approximately 60% of secondary schools provide some form of on-site counselling, with approximately 70,000–90,000 young people attending it every year in the UK.

School counselling in the UK most commonly takes a humanistic (aka ‘person-centred’) form. Here, counsellors provide clients with an empathic, non-judgmental, and supportive relationship to find their own answers to their problems. This form of counselling is not targeted towards specific mental health ‘disorders’ (for instance, depression), but adopts a more general orientation. This may make it particularly appropriate as a ‘first line’ intervention within a school context, where a diverse array of mental health challenges may exist (for instance, bereavement, bullying, and problems with parents/carers).

But does this form of school counselling actually help? Data from four small trials have provided some initial indications of effects; and qualitative research suggests that clients, parents/carers, and teachers all tend to perceive it positively. What is missing, however, is a large-scale, robust evaluation of this intervention, which looks at a range of mental health and educational outcomes, follow-up effects, and economic costs; as well as the experiences and perceptions of clients, parents/carers, and teachers.

In 2016, a team led by the University of Roehampton was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council to conduct such a study, with collaborators at the universities of Manchester and Sheffield; the London School of Economics; Metanoia Institute (London); the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy; and the National Children’s Bureau.

The Effectiveness and Cost-effectiveness Trial of School-based Humanistic Counselling (ETHOS) was conducted in 18 state-funded secondary schools in London. Recruitment was through the schools’ pastoral care teams who were briefed on the trial and asked to identify potentially eligible young people. If parental/carer consent was given, young people were then assessed by a member of the research team to see if they wanted—and assented—to participate; and to check that they had at least moderate levels of emotional symptoms. Eligible young people were then randomly assigned to one of two conditions: school-based humanistic counselling (along with access to the school’s usual pastoral care provision) (167 young people), or access to usual pastoral care alone (162 young people).

Counselling sessions were delivered on an individual, face-to-face basis, and lasted about 45 minutes. They were scheduled weekly over a period of up to 10 school weeks. The counselling was delivered by a team of 19 counsellors, all of whom were qualified to diploma level (at least two years, part time training). The counsellors received clinical supervision throughout the trial, and recordings of their practice was ‘audited’ to make sure they adhered to humanistic counselling competences.

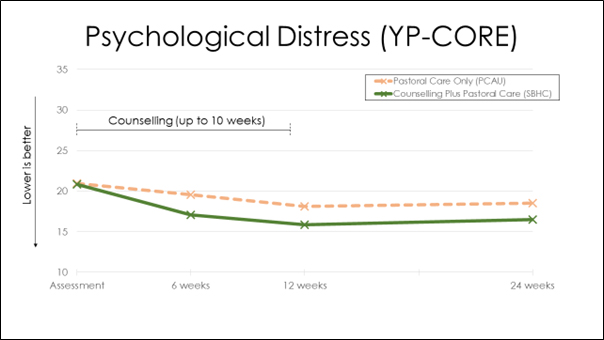

We collected data on outcome measures at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 24 weeks after assessment. We also conducted interviews with 50 of the young people in the trial--and teachers and parents/carers--to understand more of the process of change in SBHC.

The ETHOS trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) Registry. ID: ISRCTN10460622. This work was supported by funding from the Economic and Social Research Council [grant reference ES/M011933/1].

Our main finding was that, 12 weeks from assessment, those who had participated in counselling reported significantly less psychological distress than those who had not (see figure). These differences were still present 12 weeks later; and were not affected by factors such as client’s gender, age, or ethnicity. However, the differences between the two groups was relatively modest: about two points on our ‘Young Person’s CORE (YP-CORE)’ measure of psychological distress, which ranges from 0 to 40.

We also found that counselling brought about medium to large improvements on the clients’ individual goals (for instance, feeling more confident, improving their relationships with their parents/carers, or controlling their anger), and self-esteem across all time points; and small improvements in wellbeing and psychological difficulties at 12 weeks. However, the counselling had no significant effect on symptoms of anxiety and depression. It also had no effect on the young people’s willingness to engage with school; or on other educational outcomes, such as attendance and exclusion rates, number of disciplinary proceedings, and predicted grades. In addition, we found that the counselling did not bring about reductions in the use of other services, such as pastoral care support or GPs. Economically, then, the cost of the counselling was not offset by other service savings—at least not over the 24 week period.

Surprisingly, we found more ‘adverse events’—such as school exclusions and self-harm—in the counselling group. However, this may have been because they were seeing the counsellors every week, and therefore may have been more likely to report such events.

Satisfaction

When asked to rate, overall, whether the counselling was good or not, around two-thirds said that this was ‘certainly true’, 30% said that it was ‘partly true’, and about 5% said it was ‘not true’. We found similar levels of satisfaction when we analysed data from our 50 post-counselling interviews. Around half of the clients were unequivocally positive, for instance, ‘I really loved it; I loved her, I thought she was amazing’. Another 20% were then generally positive, but described one or two elements that they found less helpful. Approximately 20% said that the counselling had not helped much, but could see some positive elements to it. Finally, two of the 50 clients (4%) described the counselling in almost wholly negative terms. One of these, for instance, dropped out after only one session: ‘Just didn’t think it helped. Nothing really happened, we didn’t even speak.’

Our findings suggest that, on average, school-based humanistic counselling can help young people, with effects that persist for at least three months after the end of counselling. The counselling was most effective in helping young people improve their self-esteem and achieve personal goals; least effective at reducing mental health symptoms. In addition, it showed not effect on educational outcomes or reducing other service costs. Such averages, however, can mask differences in the way that young people responded to the counselling: around two-thirds seem to have found it wholly or mostly helpful, another 30% or so found it helped a bit; and then approximately 5% really did not like it.

Finding effective ways of addressing mental health problems in young people remains a priority for policy makers and fund holders. Our study shows that school-based humanistic counselling is a viable option, but it is not a ‘magic bullet’. Rather, it is likely to help some young people some of the time, and should be offered to young people as one out of a range of possible interventions. What is most important now is to carry out equally rigorous evaluations of alternative programmes in the UK; and to develop some understanding of which interventions are most likely to be helpful for whom.

The trial was led by Mick Cooper from the University of Roehampton. The Project Manager, Megan Stafford, and Project Administrator, Tiffany Rameswari, were also based at the University of Roehampton.

Co-investigators for the trial were Karen Cromarty (Consultant), Peter Pearce (Metanoia Institute), Charlie Duncan (British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy), Michael Barkham and Dave Saxon (University of Sheffield), Peter Bower (University of Manchester), Jeni Beecham (London School of Economics), and Stephanie Smith and Gayle Munro (National Children’s Bureau).

The study was supported by the Manchester-based UKCRC-registered Clinical Trials Unit (MAHSC-CTU).

Members of the ETHOS team celebrating end of data collection in July 2018.

A young persons’ advisory group (YPAG) and a family research advisory group (FRAG) were established which provided a link between the study and its participants and their parents/carers. The YPAG and FRAG are both made up of people who have received training from the National Children’s Bureau Research Centre in a range of research skills and have been involved in various ways throughout the study, including attending the Trial Steering Committee meetings (see below).

Three of the four members of the advisory group are pictured at their first meeting in May 2016.

A Trial Steering Committee (TSC) was established and chaired by Professor Derek Bolton. Other members of the TSC, outside of the core research team, included a counselling academic, a statistician, an economist, and members of the YPAG.

The role of the TSC was to monitor the scientific integrity of the trial and assess trial quality and conduct (in accordance with the principles of good clinical and research practice, as per the British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy, Social Research Association, and ESRC guidelines).

A Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) was also set up to review accruing trial data and to assess whether there were any safety issues that should be brought to the participants’ attention. The DMEC was independent of the core trial team and was chaired by Professor Jason Madan. Other members included an independent statistician and independent health economist.

Publications to Date

Cooper, M., Stafford, M. R., Saxon, D., Beecham, J., Bonin, E.-M., Barkham, M., Bower, P., Cromarty, K., Duncan, C., Pearce, P., Rameswari, T., & Ryan, G. (2021). Humanistic counselling plus pastoral care as usual versus pastoral care as usual for the treatment of psychological distress in adolescents in UK state schools (ETHOS): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child and Adolescent Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30363-1

Stafford, M. R., Cooper, M., Barkham, M., Beecham, J., Bower, P., Cromarty, K., Fugard, A. J. B., Jackson, C., Pearce, P., Ryder, R., & Street, C. (2018). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of humanistic counselling in schools for young people with emotional distress (ETHOS): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials, 19, 175. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2538-2

Longhurst, P., Sumner, A. L., Smith, S., Eilenberg, J., Duncan, C., & Cooper, M. (2021). ‘They need somebody to talk to’: Parents' and carers' perceptions of school-based humanistic counselling. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, n/a(n/a). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12496

Ralph, S., & Cooper, M. (2022). Brief humanistic counselling with an adolescent client experiencing obsessive compulsive difficulties: A theory-building case study. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, n/a(n/a). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12499

Ryan, G., Bhatti, K., Duncan, C., McGinnis, S., Elliott, R., & Cooper, M. (2021). Reliability and validity of an auditing tool for person-centred psychotherapy and counselling for young people: The PCEPS-YP. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12505

Presentations

Mick Cooper’s inaugural lecture, at the commencement of the ETHOS trial.

Ralph, S. Brief humanistic counselling with an adolescent client experiencing obsessive-compulsive difficulties: A theory-building case study. OCD in Society: the Future of Critical OCD Studies, 28-29 May 2021 (online). Podcast available here.

Data sharing

Quantitative, participant-level data for the ETHOS study (with data dictionary), and related documents (eg, parental consent form), are available via the ReShare UK Data Service (reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/853764/). Access requires ReShare registration.

External organisations can also request access to ETHOS data via our data sharing policy and application form.

If you are interested in analysing qualitative or quantitative data from the trial, you can also email Mick Cooper to discuss further.

Resources

Manuals, Protocols, and Plans

- SBHC Clinical Practice Manual

- SBHC Supervision Manual

- Statistical Analysis Plan

- Economic Analysis Plan

- Adverse Events Protocol

Adherence measures

- Person-centred and Experiential Psychotherapy Scale--Young Person Counselling Version (PCEPS-YP)

- Person-centred and Experiential Psychotherapy Scale--Young Person Counselling Version Short (PCEPS-YP-S)

- SBHC Supervision Adherence Scale

- BACP Competences for work with children and young people

Logs

Forms and Measures

We are planning to hold a dissemination conference for the findings of the study in summer 2021.

Due to the new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, 2018) which we’re sure you’ve already heard about, we have recently updated our privacy notice. This explains what data we collect, why we collect it, how we use it, who we share it with and other information relating to the privacy of participants’ data. This statement applies to the ETHOS project and its related project, AGENCY. For more information about GDPR in relation to either project please contact: mick.cooper@roehampton.ac.uk

SBHC, as delivered in ETHOS, was based on competences for humanistic counselling with children and young people and followed a clinical practice manual. The therapy assumes that distressed young people have the capacity to successfully address their difficulties if they can talk them through with an empathic, supportive, and qualified counsellor. School-based humanistic counsellors use a range of techniques to facilitate this process, including active listening, empathic reflections, inviting young people to access and express underlying emotions and needs, and helping clients to reflect on, and make sense of, their experiences and behaviours. Young people are also encouraged to consider the range of options that they are facing, and to make choices that are most likely to be helpful within their given circumstances. As part of the intervention, young people participating in the ETHOS trial were asked to complete the Outcome Rating Scale sessional measure. The PCEPS-YP-S measure was also used, in supervision, to explore counsellors' adherence to SBHC practice.

A brief example of school-based humanistic practice is presented below.

A more extended example of SBHC, followed by reflections by counsellor and client, is presented below.

Further Reading

Please find a list of additional readings used in the study that you may find useful:

- Baskin, T. W., Slaten, C. D., Crosby, N. R., Pufahl, T., Schneller, C. L., & Ladell, M. (2010). Efficacy of counseling and psychotherapy in schools: A meta-analytic review of treatment outcome studies. The Counseling Psychologist, 38(7), 878-903.

- Beecham, J., & Pearce, P. (2015). The ALIGN Trial: service use and costs for students using school-based counselling. Personal Social Services Research Unit Discussion Paper 2883, University of Kent.

- Cooper, M. (2009). Counselling in UK secondary schools: A comprehensive review of audit and evaluation studies. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 9(3), 137-150.

- Cooper, M. (2013). School-based counselling in UK Secondary schools: A review and critical evaluation. Lutterworth: BACP/Counselling MindEd. [Online] Available at: http://counsellingminded.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/cooper_MindEd_report.pdf

- Cooper, M., Rowland, N., McArthur, K., Pattison, S., Cromarty, K., & Richards, K. (2010). Randomised controlled trial of school-based humanistic counselling for emotional distress in young people: Feasibility study and preliminary indications of efficacy. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 4(1), 1-12.

- Cooper, M., Stewart, D., Sparks, J., & Bunting, L. (2013). School-based counselling using systematic feedback: a cohort study evaluating outcomes and predictors of change. Psychotherapy Research, 23(4), 474-488.

- Hill, A., Cooper, M., Pybis, J., Cromarty, K., Pattison, S., Spong, S., & Couchman, A. (2011). Evaluation of the Welsh School-based counselling strategy. Cardiff: Welsh Government Social Research.

- McArthur, K., Cooper, M., & Berdondini, L. (2013). School-based humanistic counseling for psychological distress in young people: Pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy Research, 23(3), 355-365.

- Pearce, P., Sewell, R., Cooper, M., Osman, S., Fugard, A.J.B., & Pybis, J. (2017). Effectiveness of school-based humanistic counselling for psychological distress in young people: Pilot randomized controlled trial with follow-up in an ethnically diverse sample. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 90, 138-155.

- Pybis, J., Cooper, M., Hill, A., Cromarty, K., Levesley, R., Murdoch, J., & Turner, N. (2014). Pilot randomised controlled trial of school-based humanistic counselling for psychological distress in young people: Outcomes and methodological reflections. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 15(4), 241-250.

- Rupani, P., Cooper, M., McArthur, K., Pybis, J., Cromarty, K., Hill, A., & Turner, N. (2013). The goals of young people in school-based counselling and their achievement of these goals. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 14(4), 306-314.

- Bhatti, K., Pauli, G., & Cooper, M. (2023). An exploration of the psychometric properties of the Barrett-Lennard Relationship Inventory (BLRI Obs-40) with young people. Person-Centered & Experiential Psychotherapies, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14779757.2023.2185279